1、你的整个训练、减脂、营养,安排,都有问题

2、其中问题最大的,是你的睡眠

一、睡眠问题,这个作息是在拿自己的生命/健康开玩笑

众所周知,人类是日落而息的,晚上6-8点以后就不应该从事相对剧烈的活动了。

强行训练,打破自然规律,导致神经过分兴奋,晚上睡不着,无异于慢性自杀。

我觉得是常识,为什么题主会不清楚呢。

口说无凭,我们还是看证据吧。

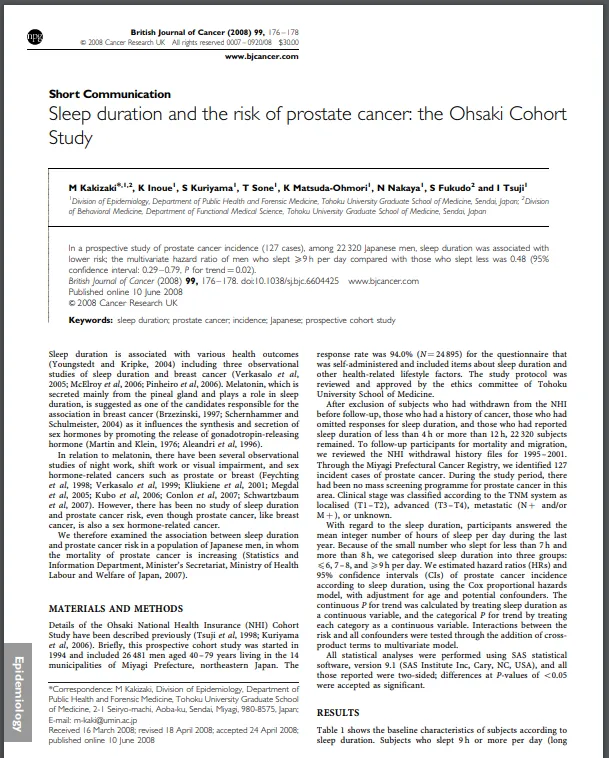

1、Kakizaki等人针对22320名日本人的研究发现,睡眠充足者发生前列腺癌的几率降低了52%[2];

2、Tatsuhiko等人针对14052人的研究发现[3],不规律作息(轮班,一会白班一会夜班)工作者前列腺癌的发病率提高200%;与之相对的是,规律作息(固定夜班)者的相关风险增加很少且不显著;

3、Liu等人在日本的进行的一项针对几百人的研究发现[1],每周工作60小时、或每日睡眠少于5小时,急性心肌梗死的发作率大幅度提高。

4、轮班工人的昼夜节律失调与心脏代谢异常[15]、代谢综合症、心血管疾病的风险增加有关[16,17,18,19]。

5、睡眠不足增减少褪黑激素的产生,扰乱昼夜节律[48],增加冠心病风险[49]、2型糖尿病风险[50]、肥胖风险[51]、抑郁症风险[52],从而增加死亡风险[53]。

值得一提的是,睡眠不足与癌症的关联,与褪黑素有密切关系[4,5,6]。

褪黑素它调节性激素的分泌[8,9],对前列腺癌和乳腺癌细胞,具有抗增殖作用[6]。

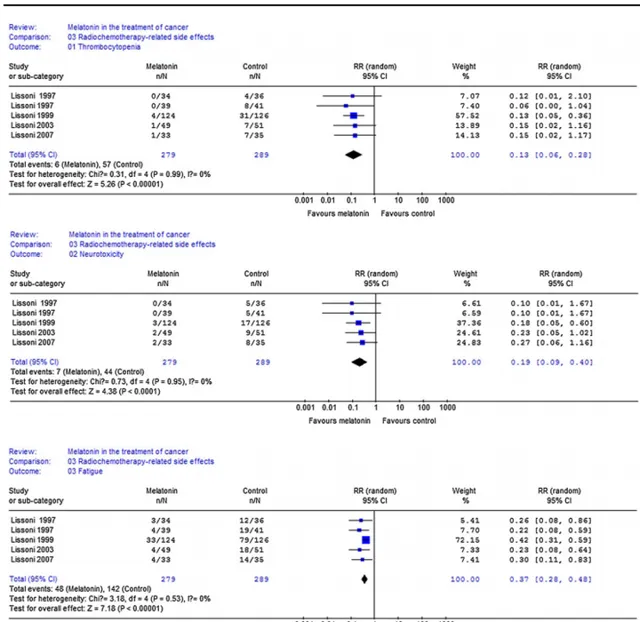

我国有些研究实验室环境中反复论证了褪黑素具有一定抗癌的作用,提倡应当在癌症治疗中作为一种辅助手段[92]。

此外,褪黑素还有维持免疫系统功能、保护DNA、抗氧化、血糖调节等功能[10]。

由于褪黑素主要在睡眠中分泌,睡眠不足会减少它的分泌[7]。

但是,我并不建议你们自己去吃褪黑素。

二、睡眠不足对增肌/减脂的显著抑制

我有14年的系统训练史,最大体重超过100KG。

在我精力充沛不太工作的时候,可以坐姿下半程100KG杠铃推举做组,4-5次组——自由重量。

根据我的个人经验:

当然,这只是我的个人经验,凡事讲证据。

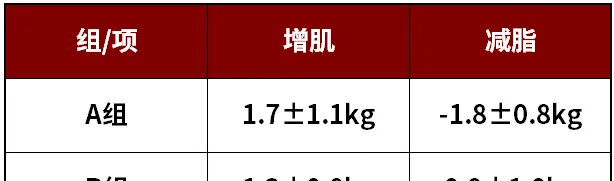

1、2020年,Rein等人研究了一群人,把他们分为2组:

A组:训练+睡眠优化(10人);

B组:训练+不优化睡眠组(12人)

也就是说,睡眠不足会抑制增肌、抑制减脂,让人又胖肌肉又少。

当然, 上面一个研究还相对温和,下面一个更典型 。

三、睡眠不足对减脂的不利

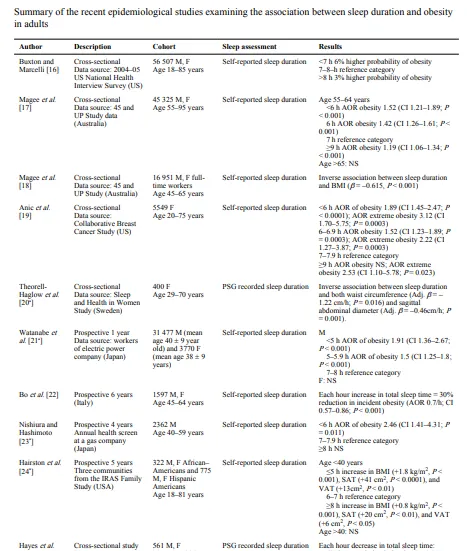

自1980年以来,全球肥胖患病率翻了一倍以上[11],肥胖的流行与睡眠时间缩短的趋势是吻合的[12]。

越来越多的证据表明,睡眠不足,会促进肥胖及其并发症发生[13,14];对于中老年人来说,睡眠时间较短导致他们的肥胖风险增加52%[21];

有趣的是,对于睡眠不足5小时的人来说,每多睡一小时,BMI就会降低0.35[20],这相当于一个1.7米身高的人瘦了1-1.5kg左右。

请注意前提:啥都不做,只是多睡觉,就会瘦。

(在我的个人经验中,瘦脸与睡眠关系特别大,连续睡得好我的脸就不肿)

总的来说,大量证据都证明了睡眠不足会导致肥胖。

四、 睡眠不足会促进食欲,让人多吃

人体内有一种激素,叫做 ghrelin ,它是一种胃肠分泌的肽类物质[97,98]。

肽,有些朋友不熟悉,没关系,至少大家都知道蛋白质:大量氨基酸由键连接在一起所组成的;其实,肽,无非就是少量的氨基酸连接在一起,可以粗略的这样理解。

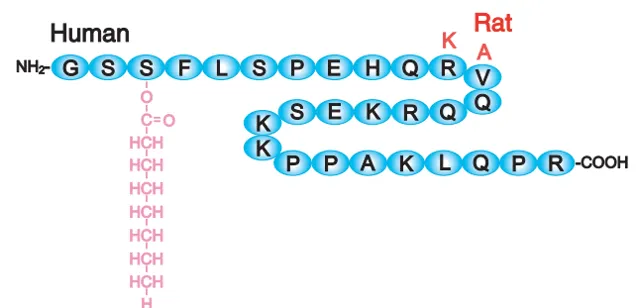

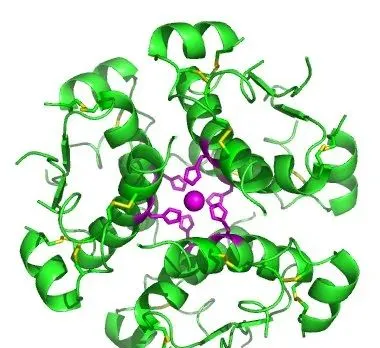

ghrelin,有人给他起了中文名叫加拉宁神经肽,它由28个氨基酸链接而成。人和老鼠的ghrelin类似,差不多长这样:

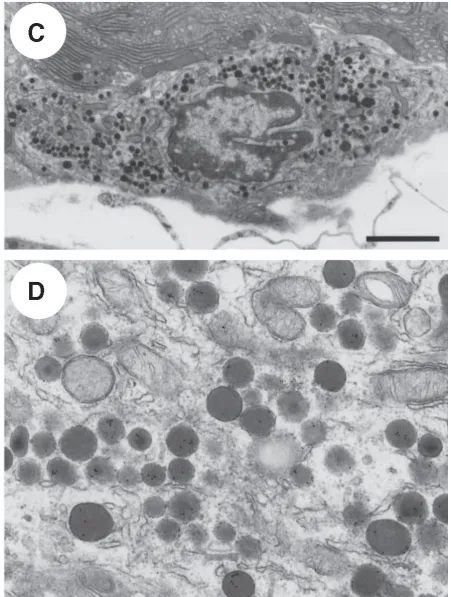

ghrelin由胃肠细胞分泌。这些细胞在高倍放大下长这样。

胃肠细胞分泌ghrelin后,由血液循环,到达下丘脑, 它会刺激下丘脑的弓核区域,从而刺激食欲 ,所以ghrelin被认为是一种刺激食欲、调剂能量平衡的激素[93,94,95,96]。

用通俗的话来说,它的作用是让你饿,让你吃,让你朝胖的方向发展,所以它也叫促饥饿素,较高水平的ghrelin有助于脂肪的保留,抑制脂肪分解[36,37,38]。

与之对应的,还有抑制食欲的激素leptin—瘦素[44],瘦素既能抑制食欲,也能增加能量消耗[27]。

大量研究发现[13,22,23,24,25],睡眠不足,ghrelin会被上调,leptin会被抑制,人倾向于吃更多东西,所以就容易胖。

Spiegel等人[26]分析了健康年轻男性的睡眠,提供了食欲素系统的示意图,它表示睡眠和进食之间的联系。一些促进食欲的神经元会调节下丘脑摄食中心,产生「进食奖赏」[22]。

也就是说,睡不好的人容易吃的更多,所以更容易胖。

五、睡眠不足还会降低代谢,减少热量消耗

从道理上说,睡不好,就不想动,没精神。

因此,证据显示,睡眠不足,身体会自发的减少运动,在白天导致嗜睡和疲劳,增加久坐行为,从而减少与运动相关的能量消耗[28];

睡眠不足还减少白天安静状态的能量消耗[42,43,44,45,46],减少能量支出[47],例如通过降低体温的方式[29](产热也需要耗能);

虽然有些研究发现睡眠不足导致夜间能量消耗增加了32%[30],但这被更多的进食所抵消了,因为睡眠不足上调了促进食欲的激素ghrelin、下调了抑制食欲的激素leptin[31,32];

例如Nedeltcheva等人[33]观察了10名超重中年人发现,睡眠不足导致ghrelin水平和饥饿感增加;

Brondel等人[34]发现12名体重正常的年轻人在夜间睡眠4小时后,热量摄入增加、饥饿感增强;

Tasali等人[35]对10名健康年轻人观察发现,与8.5小时相比,连续4天晚上只4.5小时,热量摄入增加了14%。

六、 睡眠不足还抑制脂肪分解

睡不够,对于正在进行节食、制造热量缺口的人来说很不利。

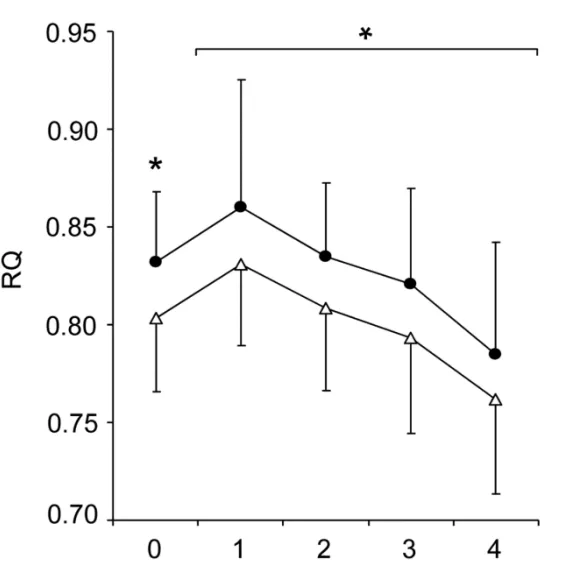

Arlet等人证实,对于节食的人来说,睡眠充足者(8.5小时,空心三角)比睡眠不足者(5.5小时,实心圆)的脂肪燃烧率更高。

下图中的RQ,是呼吸商,是一种呼吸测量技术[100]。

这种技术能通过分析能从我们呼吸的气体中来分析我们的身体是倾向于燃烧碳水供能还是燃烧脂肪供能更多[99,101]。

呼吸商越低表示燃烧脂肪越多,越接近1表示燃烧碳水更多。

通过这种技术,Arlet等人证实:

对于正在节食试图减脂的人来说,睡眠不足会大大的降低我们的减脂效果。

在Arlet等人发现,同样面临热量不足,但是睡眠不足的人减脂的量,比睡眠充足的人减少了 56%之多 [39],这也和Krotkiewski等人[40]、Rein等人的研究结论相支持。

所以,我们回过头来看,为什么题主减脂好像减不动,那就完全正常了。

七、睡眠不足,减肌

人和动物的肌肉,不是固定不动的,是在不断和成和分解,不断变化的。

生命的基本特征是新陈代谢[60],不断更新组织:旧的组织不断死亡(被分解)[61],新的组织不断产生(被合成)。

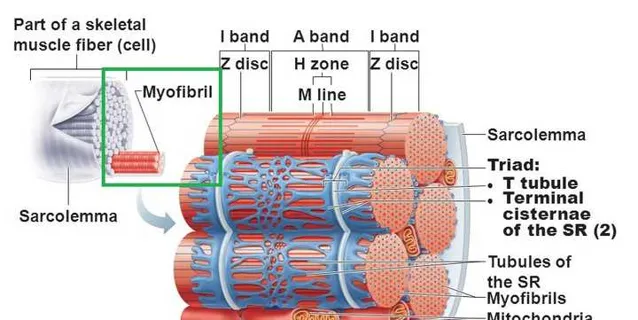

人体肌纤维中,有一些更细的结构,叫肌原纤维-myofibrils(下图中的绿框)。

肌原纤维的内部是肌蛋白[54,55];

爱好者们经常说,你增肌了,或者你肌肉围度掉了,其实这就是因为肌原纤维中的蛋白质增加了[56]、或者减少了[57]。

当然,肌原纤维中的蛋白质有很多种[58,59],我们不铺开说,在这就用一个「肌蛋白」来统称。

我们的肌肉中, 肌肉大小变化取决于肌肉中的蛋白质分解和合成的差值 [62,108,109]。

在常态下,它们不断被分解、不断被合成,维持平衡,我们的肌肉大小就不变。

合成>分解=正平衡=增肌=肌纤维变粗

分解>合成=负平衡=减肌=肌纤维变细

这些内容跟本文的关系在于:睡眠不足,都跟肌肉的「净平衡」有关。

有许多证据表明,睡眠于维持肌肉的量相当重要[103,104],在睡眠<7小时每晚、或自称睡眠质量较低的人中,骨骼肌量下降、骨骼肌流失相当较为常见[105,106,107]。

在持续2周,每晚5.5小时的睡眠剥夺研究中,人类也表现出了大幅度的骨骼肌流失[90]。

上个世纪80年代就已经证明了[110],连续3天睡眠不足,骨骼肌就会明显加速流失(尿液中的氮排放量)显著增加。

八、 睡眠不足升高皮质醇水平

我们在上面刚刚讲了,肌肉大小是个动态平衡过程,取决于肌肉的合成与分解之间的差值。

我们从一些数据看到,睡眠不足者的肌肉量和肌肉质量都较低[90,91],睡眠不足是导致肌肉萎缩的重要因素之一[64]。

因为,睡眠不足会导致皮质醇水平升高[63,65]。

而皮质醇的作用刚好就是抑制肌肉合成、促进肌肉分解[66]。

William等人测试了近140民游牧民族男子发现,皮质醇水平越高,肌肉横截面积越小,两者呈负相关关系[102]。

九、 睡眠不足扰乱合成代谢激素的分泌

在睡眠剥夺的研究中,个体的分解代谢激素(如皮质醇)被上调、合成代谢激素(如睾酮、IGF-1)等被下调[67,68]。

尤其是IGF-1,它是非常重要的促进肌肉增长的激素[69,70,71,72,73,74];

IGF-1对于维持肌肉的能量代谢[80、81]、对于肌蛋白合成极为重要[75,76,77,78],甚至于有些研究者认为它是必不可少的[79]。

这些,我们在之前的文章中已经写过,就不赘述了。

生长激素到底能够增加肌纤维数量吗?

十、 睡眠不足促成胰岛素抵抗

我们在之前的文章中也说过,胰岛素是一种重要的合成代谢激素。

既然只有蛋白质才能转化肌肉为什么增肌期间还要摄入大量碳水?

胰岛素同时促进脂肪、碳水、氨基酸的吸收,非常有助于增肌[82,83]。

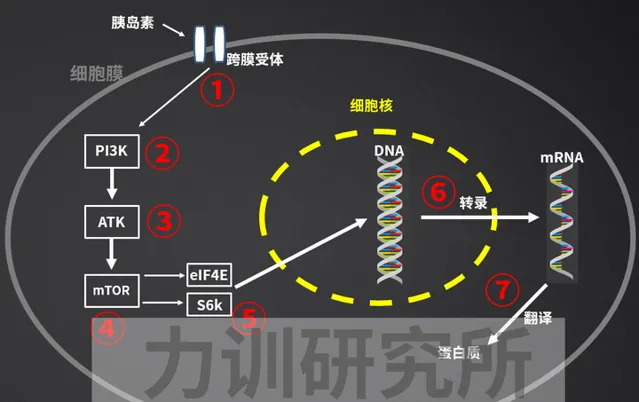

至于为什么胰岛素能增肌,我们在之前的文章中也解释过,这里稍微复习一下:

胰岛素增肌的路径是首先激活IRS-1和2,然后按顺序激活PI3K-Akt-mTOR-S6K,最后刺激DNA转录[84,85,86,87];

对本文来说,睡眠不足可促进胰岛素抵抗[88],抵消胰岛素促进DNA转录(合成肌蛋白)的作用,从而限制肌肉增长[89]。

所以,我们能看到有些支持性数据显示,1-2个晚上的完全睡眠剥夺,导致24小时的尿氮排泄的增加。

众所周知,蛋白质分解是人体脑叶排出氮的来源,一般每6.25g蛋白质含有1g的氮。

所以,尿液中氮出量的增加,意味着着肌肉的分解增加,肌肉的净变化偏向于损失。

十一、晚上睡得少,尽量白天补一些

训练到一定强度的朋友都知道,如果要保持高强度的训练,比如深蹲在150-180KG做组、卧推100KG十几个一组的水平上,晚上8小时左右是不够的。

这种情况下,大家都感觉到中午的睡眠至关重要:全靠中午午睡来「回血」,以支撑下午下班后的训练。

当然,上述只是民间经验,其实科学也证实了这一点。

Water等人进行了研究[111],他让受试者晚上只睡4个小时(23:00-3:00),然后让他们在午后13:00-13:30可以睡半小时(打盹组)或者是不睡(对照组)。

打盹组的冲刺时间得到了改善,平均2米冲刺时间从1.060秒下降到1.019秒;20米短跑的平均时间从3.971s下降到3.878s。

结果表明午后小睡可以提高部分睡眠不足后精神状态和和运动表现。

小结:

1、训练不宜在晚上进行,如果影响了睡眠,得不偿失,很伤

2、睡不够,增肌、减脂的效果都大打折扣

3、睡眠的重要性,以我个人经验而言,凌驾于训练和饮食之上

4、如果夜间睡不够,白天午睡至关重要

5、减脂不能一味低碳,低碳减脂不合理也不科学,数据很多,以后有空讲

推荐阅读:

有哪些是你健身久了知道的事?

肉崽:力训研究所课程介绍

肉崽:力训研究所线上期刊介绍

References

1. Y Liu, H Tanaka, The Fukuoka Heart Study Group.Overtime work, insufficient sleep, and risk of non-fatal acute myocardial infarction in Japanese men.Occup Environ Med 2002;59:447–451.

2. Kakizaki M, Inoue K, Kuriyama S, et al. Sleep duration and the risk of prostate cancer: the Ohsaki Cohort Study. Br J Cancer. 2008;99:176–8.

3. Tatsuhiko Kubo 1 , Kotaro Ozasa, Kazuya Mikami, Kenji Wakai, Yoshihisa Fujino, Yoshiyuki Watanabe, Tsuneharu Miki, Masahiro Nakao, Kyohei Hayashi, Koji Suzuki, Mitsuru Mori, Masakazu Washio, Fumio Sakauchi, Yoshinori Ito,

Takesumi Yoshimura, Akiko Tamakoshi.Prospective cohort study of the risk of prostate cancer among rotating-shift workers: findings from the Japan collaborative cohort study.Am J Epidemiol. 2006 Sep 15;164(6):549-55.

4. Brzezinski A (1997) Melatonin in humans. N Engl J Med 336: 186 – 195 Conlon M, Lightfoot N, Kreiger N (2007) Rotating shift work and risk of prostate cancer. Epidemiology 18: 182 – 183

5. Schernhammer ES, Schulmeister K (2004) Melatonin and cancer risk: does light at night compromise physiologic cancer protection by lowering serum melatonin levels? Br J Cancer 90: 941 – 943

6. Shiu SY (2007) Towards rational and evidence-based use of melatonin in prostate cancer prevention and treatment. J Pineal Res 43: 1–9

7. Wehr TA (1991) The durations of human melatonin secretion and sleep respond to changes in daylength (photoperiod). J Clin Endocrinol Metab 73: 1276 – 1280

8. Martin JE, Klein DC (1976) Melatonin inhibition of the neonatal pituitary response to luteinizing hormone-releasing factor. Science 191: 301 – 302

9. Aleandri V, Spina V, Morini A (1996) The pineal gland and reproduction. Hum Reprod Update 2: 225 – 235

10. B Claustrat, J Leston Melatonin: Physiological effects in humans.Neurochirurgie. Apr-Jun 2015;61(2-3):77-84. doi: 10.1016/j.neuchi.2015.03.002. Epub 2015 Apr 20.

11. Finucane MM, Stevens GA, Cowan MJ, et al. National, regional, and global trends in body-mass index since 1980: systematic analysis of health examination surveys and epidemiological studies with 960 country-years and 9.1 million participants. Lancet. 2011; 377:557–567.

12. CDC. Unhealthy sleep-related behaviors – 12 States, 2009. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2011; 60:233–238.

13. Morselli L, Leproult R, Balbo M, Spiegel K. Role of sleep duration in the regulation of glucose metabolism and appetite. Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2010; 24:687–702.

14. Knutson KL. Sleep duration and cardiometabolic risk: a review of the epidemiologic evidence. Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2010; 24:731–743.

15. Scheer FA, Hilton MF, Mantzoros CS, Shea SA. Adverse metabolic and cardiovascular consequences of circadian misalignment. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009; 106:4453–4458.

16. Bass J, Takahashi JS. Circadian integration of metabolism and energetics. Science. 2010; 330:1349–1354.

17. Esquirol Y, Bongard V, Mabile L, et al. Shift work and metabolic syndrome: respective impacts of job strain, physical activity, and dietary rhythms. Chronobiol Int. 2009; 26:544–559.

18. De Bacquer D, Van Risseghem M, Clays E, et al. Rotating shift work and the metabolic syndrome: a prospective study. Int J Epidemiol. 2009; 38:848–854.

19. Garaulet M, Ordovas JM, Madrid JA. The chronobiology, etiology and patho-physiology of obesity. Int J Obes (Lond). 2010; 34:1667–1683.

20. Cappuccio, F.; Miller, M. The epidemiology of sleep and cardiovascular risk and disease.. In: Cappuccio, F.; Miller, M.; Lockley, S., editors. Sleep, health and society: from aetiology to public health. Oxford University Press; Oxford: 2010. p. 83-110.

21. Magee CA, Caputi P, Iverson DC. Is sleep duration associated with obesity in older Australian adults? J Aging Health. 2010; 22:1235–1255.

22. Pannain S, Miller A, Van Cauter E. Sleep loss, obesity and diabetes: prevalence, association and emerging evidence for causation. Obes Metab-Milan. 2008; 4:28–41.

23. Spiegel K, Leproult R, L'Hermite-Baleriaux M, et al. Leptin levels are dependent on sleep duration: relationships with sympathovagal balance, carbohydrate regulation, cortisol, and thyrotropin. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2004; 89:5762–5771.

24. Spiegel K, Tasali E, Penev P, Van Cauter E. Brief communication: sleep curtailment in healthy young men is associated with decreased leptin levels, elevated ghrelin levels, and increased hunger and appetite. Ann Intern Med. 2004; 141:846–850.

25. Van Cauter E, Spiegel K, Tasali E, Leproult R. Metabolic consequences of sleep and sleep loss. Sleep Med. 2008; 9(Suppl 1):S23–S28.

26. Spiegel K, Tasali E, Leproult R, et al. Twenty-four-hour profiles of acylated and total ghrelin: relationship with glucose levels and impact of time of day and sleep. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2011; 96:486–493.

27. Scarpace PJ, Matheny M, Pollock BH, Tumer N. Leptin increases uncoupling protein expression and energy expenditure. Am J Physiol. 1997; 273(1 Pt 1):E226–E230.

28. Schmid SM, Hallschmid M, Jauch-Chara K, et al. Short-term sleep loss decreases physical activity under free-living conditions but does not increase food intake under time-deprived laboratory conditions in healthy men. Am J Clin Nutr. 2009; 90:1476–1482.

29. Vaara J, Kyrolainen H, Koivu M, et al. The effect of 60-h sleep deprivation on cardiovascular regulation and body temperature. Eur J Appl Physiol. 2009; 105:439–444.

30. Jung CM, Melanson EL, Frydendall EJ, et al. Energy expenditure during sleep, sleep deprivation and sleep following sleep deprivation in adult humans. J Physiol. 2011; 589(Pt 1):235–244.

31. Mullington JM, Chan JL, Van Dongen HP, et al. Sleep loss reduces diurnal rhythm amplitude of leptin in healthy men. J Neuroendocrinol. 2003; 15:851–854.

32. Schmid SM, Hallschmid M, Jauch-Chara K, et al. A single night of sleep deprivation increases ghrelin levels and feelings of hunger in normal-weight healthy men. J Sleep Res. 2008; 17:331–334.

33. Nedeltcheva AV, Kilkus JM, Imperial J, et al. Insufficient sleep undermines dietary efforts to reduce adiposity. Ann Intern Med. 2010; 153:435–441.

34. Brondel L, Romer MA, Nougues PM, et al. Acute partial sleep deprivation increases food intake in healthy men. Am J Clin Nutr. 2010; 91:1550–1559.

35. Tasali E, Broussard J, Day A, et al. Sleep curtailment in healthy young adults is associated with increased ad lib food intake [meeting abstract]. Sleep. 2009; 32(Suppl):A163.

36. Tschop M, Smiley DL, Heiman ML. Ghrelin induces adiposity in rodents. Nature. 2000; 407(6806): 908–913.

37. Nogueiras R, Tschop MH, Zigman JM. Central nervous system regulation of energy metabolism: ghrelin versus leptin. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2008; 1126:14–19.

38. Rodriguez A, Gomez-Ambrosi J, Catalan V, et al. Acylated and desacyl ghrelin stimulate lipid accumulation in human visceral adipocytes. Int J Obes (Lond). 2009; 33(5):541–552.

39. Arlet V. Nedeltcheva, MD1, Jennifer M. Kilkus, MS2, Jacqueline Imperial, RN2, Dale A. Schoeller, PhD3, and Plamen D. Penev, MD, PhD.Insufficient sleep undermines dietary efforts to reduce adiposity.Ann Intern Med. 2010 October 5; 153(7): 435–441.

40. Krotkiewski M, Landin K, Mellstrom D, Tolli J. Loss of total body potassium during rapid weight loss does not depend on the decrease of potassium concentration in muscles. Different methods to evaluate body composition during a low energy diet. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 2000; 24(1):101–107.

41. Scrimshaw NS, Habicht JP, Pellet P, Piche ML, Cholakos B. Effects of sleep deprivation and reversal of diurnal activity on protein metabolism of young men. Am J Clin Nutr. 1966; 19(5): 313–319.

42. Ravussin E, Burnand B, Schutz Y, Jequier E. Energy expenditure before and during energy restriction in obese patients. Am J Clin Nutr. 1985; 41(4):753–759.

43. Leibel RL, Rosenbaum M, Hirsch J. Changes in energy expenditure resulting from altered body weight. New England Journal of Medicine. 1995; 332(10):621–628.

44. Rosenbaum M, Goldsmith R, Bloomfield D, et al. Low-dose leptin reverses skeletal muscle, autonomic, and neuroendocrine adaptations to maintenance of reduced weight. J Clin Invest. 2005; 115(12):3579–3586.

45. Landsberg L. Feast or famine: the sympathetic nervous system response to nutrient intake. Cell Mol Neurobiol. 2006; 26(4–6):497–508.

46. Redman LM, Heilbronn LK, Martin CK, et al. Metabolic and behavioral compensations in response to caloric restriction: implications for the maintenance of weight loss. PLoS One. 2009; 4(2):e4377.

47. Schmid SM, Hallschmid M, Jauch-Chara K, et al. Short-term sleep loss decreases physical activity under free-living conditions but does not increase food intake under time-deprived laboratory conditions in healthy men. Am J Clin Nutr. 2009; 90(6):1476–1482.

48. Medic G., Wille M., Hemels M.E. Short- and long-term health consequences of sleep disruption. Nat. Sci. Sleep. 2017;9:151–161.

49. Lao X.Q., Liu X., Deng H., Chan T., Ho K.F., Wang F., Vermeulen R., Tam T., Wong M.C., Tse L.A., et al. Sleep quality, sleep duration, and the risk of coronary heart disease: A prospective cohort study with 60, 586 adults. J. Clin. Sleep Med. 2018;14:109–117.

50. Lou P., Chen P., Zhang L., Zhang P., Yu J., Zhang N. Relation of sleep quality and sleep duration to type 2 diabetes: A population-based cross-pal survey. BMJ. 2012;2:e000956.

51. Nedeltcheva A.V., Scheer F.A. Metabolic effects of sleep disruption, links to obesity and diabetes. Curr. Opin. Endocrinol. Diabetes Obes. 2014;21:293–298.

52. Leary K.O., Bylsma L.M., Rottenberg J., Leary K.O., Bylsma L.M., Why J.R. Why might poor sleep quality lead to depression? A role for emotion regulation regulation. Cogn. Emot. 2016;31:1698–1706.

53. Crowley K. Sleep and sleep disorders in older adults. Neuropsychol. Rev. 2011;21:41–53.

54. N Narayanan, J Eapen.Protein synthesis by rat cardiac muscle myofibrils.Biochim Biophys Acta. 1973 Jun 23;312(2):413-25.

55. Kono,Fumiaki,Shimamoto,Yuta,Ishiwata,Shin'ichi.1P246 Effect of lattice spacing on SPOC of skeletal myofibrils(8. Muscle contraction and muscle protein,Poster Session,Abstract,Meeting Program of EABS & BSJ 2006)

56. D L, Pak-Loduca, K A Obert, KE Yarasheski.Resistance exercise acutely increases MHC and mixed muscle protein synthesis rates in 78-84 and 23-32 yr olds.Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2000 Apr;278(4):E620-6.

57. Ruowei, Li.The temporal control of load-dependent anabolic and catabolic pathways in human extensor muscles.Manchester Metropolitan University

58. S Winegrad.Myosin-Binding Protein C (MyBP-C) in Cardiac Muscle and Contractility.Molecular and Cellular Aspects of Muscle Contraction.

59. C M Rembold, R A Murphy.Myoplasmic calcium, myosin phosphorylation, and regulation of the crossbridge cycle in swine arterial smooth muscle.Circ Res. 1986 Jun;58(6):803-15.

60. SAS Gropper,JL Smith,J Groff.Advanced Nutrition and Human Metabolism.GROPPER, Sareen Annora Stepnick, Jack L. SMITH and James L. GROFF. Advanced nutrition and human metabolism. 5th ed. United States: Wadsworth/Cengage Learning, 2009. xvii, 600. ISBN 9780495116578.

61. T P Stein, M D Schluter.Human skeletal muscle protein breakdown during spaceflight.Am J Physiol. 1997 Apr;272(4 Pt 1):E688-95.

62. Atherton PJ, Phillips BE, Wilkinson DJ.Exercise and Regulation of Protein Metabolism.Prog Mol Biol Transl Sci. 2015;135:75–98.

63. Banks S., Dinges D.F. Behavioral and physiological consequences of sleep restriction. J. Clin. Sleep Med. 2007;3:519–528.

64. Piovezan R.D., Abucham J., dos Santos R.V.T., Mello M.T., Tufik S., Poyares D. The impact of sleep on age-related sarcopenia: Possible connections and clinical implications. Ageing Res. Rev. 2015;23:210–220.

65. Goodin B.R., Smith M.T., Quinn N.B., King C.D., McGuire L. Poor sleep quality and exaggerated salivary cortisol reactivity to the cold pressor task predict greater acute pain severity in a non-clinical sample. Biol. Psychol. 2012;91:36–41.

66. Peeters G.M.E.E., Van Schoor N.M., Van Rossum E.F.C., Visser M., Lips P.T.A.M. The relationship between cortisol, muscle mass and muscle strength in older persons and the role of genetic variations in the glucocorticoid receptor. Clin. Endocrinol. (Oxf.) 2008;69:673–682.

67. Everson CA, Crowley WR.Reductions in circulating anabolic hormones induced by sustained sleep deprivation in rats. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2004 Jun; 286(6):E1060-70.

68. von Treuer K, Norman TR, Armstrong SM. Overnight human plasma melatonin, cortisol, prolactin, TSH, under conditions of normal sleep, sleep deprivation, and sleep recovery. J Pineal Res.

69. Tadashi Yoshida1,Patrice Delafontaine.Mechanisms of IGF-1-Mediated Regulation of Skeletal Muscle Hypertrophy and Atrophy.Cells. 2020 Sep;9(9).

70. Baker J, Liu JP, Robertson EJ, Efstratiadis A. Role of insulin-like growth factors in embryonic and postnatal growth. Cell 75: 73– 82, 1993.

71. Florini JR, Ewton DZ, Coolican SA. Growth hormone and the insulin-like growth factor system in myogenesis. Endocr Rev 17:481–517, 1996.

72. Galvin CD, Hardiman O, Nolan CM. IGF-1 receptor mediates differentiation of primary cultures of mouse skeletal myoblasts. Mol Cell Endocrinol 200: 19 –29, 2003.

73. Liu JP, Baker J, Perkins AS, Robertson EJ, Efstratiadis A. Mice carrying null mutations of the genes encoding insulin-like growth factor I(Igf-1) and type 1 IGF receptor (Igf1r). Cell 75: 59 –72, 1993.

74. Powell-Braxton L, Hollingshead P, Warburton C, Dowd M, PittsMeek S, Dalton D, Gillett N, Stewart TA. IGF-I is required for normal embryonic growth in mice. Gene Dev 7: 2609 –2617, 1993.

75. Rommel C., Bodine S.C., Clarke B.A., Rossman R., Nunez L., Stitt T.N., Yancopoulos G.D., Glass D.J. Mediation of IGF-1-induced skeletal myotube hypertrophy by PI(3)K/Akt/mTOR and PI(3)K/Akt/GSK3 pathways. Nat. Cell Biol. 2001;3:1009–1013.

76. Peng X.D., Xu P.Z., Chen M.L., Hahn-Windgassen A., Skeen J., Jacobs J., Sundararajan D., Chen W.S., Crawford S.E., Coleman K.G., et al. Dwarfism, impaired skin development, skeletal muscle atrophy, delayed bone development, and impeded adipogenesis in mice lacking Akt1 and Akt2. Genes Dev. 2003;17:1352–1365.

77. Bodine S.C., Latres E., Baumhueter S., Lai V.K., Nunez L., Clarke B.A., Poueymirou W.T., Panaro F.J., Na E., Dharmarajan K., et al. Identification of ubiquitin ligases required for skeletal muscle atrophy. Science. 2001;294:1704–1708.

78. Pallafacchina G., Calabria E., Serrano A.L., Kalhovde J.M., Schiaffino S. A protein kinase B-dependent and rapamycin-sensitive pathway controls skeletal muscle growth but not fiber type specification. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2002;99:9213–9218.

79. Glass D.J. Molecular mechanisms modulating muscle mass. Trends Mol. Med. 2003;9:344–350.

80. Bassil MS, Gougeon R. Muscle protein anabolism in type 2 diabetes. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care. 2013;16:83–88.

81. Morley JE. Diabetes, sarcopenia, and frailty. Clin Geriatr Med. 2008;24:455–469.

82. Biolo G, Declan R, and Wolfe RR. Physiologic hyperinsulinemia stimulates protein synthesis and enhances transport of selected amino acids in human skeletal muscle. J Clin Invest 95: 811–819, 1995

83. Biolo G, Williams BD, Declan Fleming RY, and Wolfe RR. Insulin action on muscle protein kinetics and amino acid transport during recovery after resistance exercise. Diabetes 48: 949– 957, 1999.

84. Hillier T, Long W, Jahn L, Wei L, and Barrett EJ. Physiological hyperinsulinemia stimulates p70S6k phosphorylation in human skeletal muscle. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 85: 4900–4904, 2000.

85. Farrell PA, Hernandez JM, Fedele MJ, Vary TC, Kimball SR, and Jefferson LS. Eukaryotic initiation factors and protein synthesis after resistance exercise in rats. J Appl Physiol 88: 1036–1042, 2000.

86. Fluckey JD, Vary TC, Jefferson LS, Evans WJ, and Farrell PA. Insulin stimulation of protein synthesis in rat skeletal muscle following resistance exercise is maintained with advancing age. J Gerontol Biol Sci 51A: B323–B330, 1996.

87. Verdu J, Buratovich MA, Wilder EL, and Birnbaum MJ. Cell-autonomous regulation of cell and organ growth in Drosophila by Akt/PKB. Nature Cell Biol 1: 500–506, 1999.

88. Nedeltcheva AV, Kilkus JM, Imperial J, Schoeller DA, Penev PD. Insufficient sleep undermines dietary efforts to reduce adiposity. Ann Intern Med. 2010;153:435–441.

89. Kant GJ, Genser SG, Thorne DR, Pfalser JL, Mougey EH. Effects of 72 hour sleep deprivation on urinary cortisol and indices of metabolism. Sleep. 1984;7:142–146.

90. Nedeltcheva AV, Kilkus JM, Imperial J, Schoeller DA, Penev PD. Insufficient sleep undermines dietary efforts to reduce adiposity. Ann Intern Med. 2010;153:435–441.

91. Kant GJ, Genser SG, Thorne DR, Pfalser JL, Mougey EH. Effects of 72 hour sleep deprivation on urinary cortisol and indices of metabolism. Sleep. 1984;7:142–146.

92. Ye-min Wang. Bao-zhe Jin. Fang Ai. Chang-hong Duan. Yi-zhong Lu. Ting-fang Dong. Qing-lin Fu.The eYcacy and safety of melatonin in concurrent chemotherapy or radiotherapy for solid tumors: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials.

93. van der Lely AJ. 2009. Ghrelin and new metabolic frontiers. Horm Res 71(Suppl 1):129–133

94. Gasco V, Beccuti G, Marotta F, Benso A, Granata R, Broglio F, Ghigo E. 2010. Endocrine and metabolic actions of ghrelin. Endocr Dev 17:86–95

95. Granata R, Baragli A, Settanni F, Scarlatti F, Ghigo E. 2010. Unraveling the role of the ghrelin gene peptides in the endocrine pancreas. J Mol Endocrinol 45:107–118

96. Lim CT, Kola B, Korbonits M, Grossman AB. 2010. Ghrelin's role as a major regulator of appetite and its other functions in neuroendocrinology. Prog Brain Res 182:189–205

97. Kojima M, Hosoda H, Date Y, Nakazato M, Matsuo H, Kangawa K. 1999. Ghrelin is a growth-hormone-releasing acylated peptide from stomach. Nature 402:656–660

98. Masayasu Kojima, Kenji Kangawa.Ghrelin: structure and function.Physiol Rev. 2005 Apr;85(2):495-522.

99. Schutz Y. Abnormalities of fuel utilization as predisposing to the development of obesity in humans. Obes Res. (1995) 3 (Suppl. 2):173S−8S.

100. Respiratory Quotient.978-3-540-36065-0.

101. L.GARBY, A.ASTRUP.The relationship between the respiratory quotient and the energy equivalent of oxygen during simultaneous glucose and lipid oxidation and lipogenesis.First published: March 1987

102. William D Lukas, Benjamin C Campbell, Kenneth L Campbell.Urinary cortisol and muscle mass in Turkana men.Am J Hum Biol. Jul-Aug 2005;17(4):489-95.

103. Nedeltcheva AV, Kilkus JM, Imperial J, Schoeller DA & Penev PD (2010). Insufficient sleep undermines dietary efforts to reduce adiposity. Ann Intern Med 153, 435–441.

104. Dattilo M, Antunes HK, Medeiros A, Monico‐Neto M, Souza Hde S, Lee KS, Tufik S & de Mello MT (2012). Paradoxical sleep deprivation induces muscle atrophy. Muscle Nerve 45, 431–433.

105. Chien MY, Wang LY & Chen HC (2015). The relationship of sleep duration with obesity and sarcopenia in community‐dwelling older adults. Gerontology 61, 399–406.

106. Buchmann N, Spira D, Norman K, Demuth I, Eckardt R & Steinhagen‐Thiessen E (2016). Sleep, muscle mass and muscle function in older people. Dtsch Arztebl Int 113, 253–260.

107. Hu X, Jiang J, Wang H, Zhang L, Dong B & Yang M (2017). Association between sleep duration and sarcopenia among community‐dwelling older adults: a cross‐pal study. Medicine (Baltimore) 96, e6268.

108. Rennie MJ (1985). Muscle protein turnover and the wasting due to injury and disease. Br Med Bull 41, 257–264.

109. Gibson JN, Halliday D, Morrison WL, Stoward PJ, Hornsby GA, Watt PW, Murdoch G & Rennie MJ (1987). Decrease in human quadriceps muscle protein turnover consequent upon leg immobilization. Clin Sci (Lond) 72, 503–509.

110. Kant GJ, Genser SG, Thorne DR, Pfalser JL & Mougey EH (1984). Effects of 72 h sleep deprivation on urinary cortisol and indices of metabolism. Sleep 7, 142–146.

111. J Waterhouse, G Atkinson, B Edwards, T Reilly The role of a short post-lunch nap in improving cognitive, motor, and sprint performance in participants with partial sleep deprivation.J Sports Sci. 2007 Dec;25(14):1557-66.

112. Amber Brooks, Leon Lack.A brief afternoon nap following nocturnal sleep restriction: which nap duration is most recuperative? Sleep. 2006 Jun;29(6):831-40.